Haggadah Bites: The Bread of Poverty

The Maggid portion of the Haggadah opens with a statement in Aramaic,

which doesn't appear in the Talmud but dates back at least as far as the

Geonic period. It appears in the Seder of Rabbi Amram (9th C. head of the Sura academy in Babylonia). Here's the text, followed by two questions and reflections.

When the Torah refers to matzah, it's talking about what the Israelites ate while leaving Egypt, when they didn't have time to wait around for the dough to rise, etc. But if that were the matzah under discussion, not only should the text have said that it's the bread we ate "while leaving Egypt" rather than "in the land of Egypt," but it would rightly be called the "bread of freedom" rather than the "bread of poverty."

This matzah we hold up represents something the Torah doesn't actually speak about, an unleavened bread eaten while enslaved, hence "the bread of poverty" eaten "in the land of Egypt." Why does the Haggadah refer to matzah that's different from the one everyone knows about in the Exodus story? And why suppose that our ancestors even ate matzah at all during slavery?

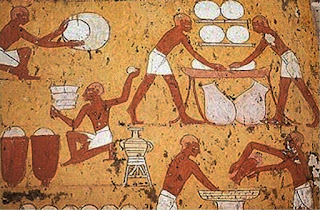

Ancient Egypt was famous for its fermented grain technology, perfecting the use of sourdough starter (se'or in Hebrew) and eventually isolating yeast cultures. It was an important craft and trade. There were royal bread makers. The type of bread you ate went along with your status. Leavened breads made with fine flour were a high society item, and they were used in ritual offerings to the gods.

Although the Torah likewise calls for solet (fine flour) in the mincha sacrifice, it prohibits using chametz (leaven) in sacrifices. According to Jacob Milgrom (Anchor Yale Bible, Leviticus Vol I, pp. 188-9), the reason for this prohibition is that chametz was considered a symbol of "corruption." But perhaps that stems in part from a perception about Egyptian practices being corrupt, and leaven being symbolic of Egypt. And of course the Torah also prohibits the consumption of leaven during Passover. Not only that, but it warns against seeing or finding leavening agents in our homes, lest we be "cut off" from the people. Perhaps these laws are less a reflection of the "leaving Egypt" aspect of matzah, explicit in the Torah, and have more to do with the implicit "Egyptian society" associations of chametz.

The Torah's stringency about leaven may be saying that it's simply not fitting to celebrate our liberation from Egypt while at the same time partaking of the quintessential Egyptian product. Perhaps it would be something like eating bratwurst and sauerkraut, or other iconic German foods, during a time specifically set aside to commemorate the liberation from Auschwitz - an act of dis-identifying with the Jewish people. In the same way, eating leaven on Passover might have been viewed as "cutting oneself off" from the people.

But it also explains why matzah here is called the "bread of poverty," not the "bread of freedom." This particular bread is symbolic of the underclass of Egypt - the poor and enslaved. I say "symbolic," as opposed to asserting that the Egyptian underclass only ate unleavened bread. Surely they ate chametz, simply by allowing their dough to stand for 18 minutes, and they used se'or/sourdough starter, as evidenced by the Torah telling the Israelites to remove the se'or from their homes. But matzah is physically "lowly" bread, "impoverished" in both form and taste, and hence symbolic of the slave class.

It's a beautiful transformation then that this bread ended up, by way of the exodus, representing freedom. It is freedom not only in the sense of being eaten "on the way out" of Egypt, but freedom also by not being chametz and thereby constituting a rejection of that which symbolizes Egyptian society, a civilization we recall for its systematic enslavement and brutality.

One might in fact argue that, living as we do with full access to a sovereign Jewish state after 2000 years, that it's not only incongruous, negating historical reality, but a show of extraordinary ingratitude to say the statement, "Now we are here; next year in the land of Israel."

But of course such an interpretation ignores the preceding statement, "Now we are slaves; next year, free people." Meaning, both statements are in the frame of make-believe, imagining ourselves to be slaves in Egypt. It's like the statement said later in the Haggadah: "If the Holy One, blessed be He, had not taken our ancestors out of Egypt, then we, our children and our children's children would have remained enslaved to Pharaoh in Egypt." Would we really? 3,300 years later, people around the world would be on Facebook, planning manned voyages to Mars, and watching the Kardashians, and meanwhile in Egypt there would still be a Pharaoh with us as his slaves? Obviously not. It's a statement of severity that's intended to set the mood, to put the image in our minds of our families, our children, being slaves.

The point of the Passover Seder, and recounting the narrative of the exodus from Egypt, is not to achieve maximal historical veracity and authenticity, but to ritually recall our national story, the way we choose to remember it, and that refers both to "what" we say and "how" we say it.

Think about the last of the four questions: "On all nights we eat sitting upright or reclining, and on this night we all recline."

Here's a place where we truly feel the gap in history. Unless we're talking TV dinners on the sofa, very few people eat reclining. If anything, eating while lying down reminds us of being infirmed, sickly. We’re so used to eating upright that it seems strange and even awkward to try to eat while reclining. Even the pillow we add to our chairs doesn't necessarily make it more comfortable or "luxurious." And to sit in a chair and lean to the left out into the air, when drinking the four cups and eating matzah, is truly bizarre. The "authentic" thing to do would be to lie down on one’s side and eat. The conceptually "meaningful" thing to do would be to eat in the most comfortable, luxurious way possible, which ironically for most people would mean sitting upright in a chair. Leaning awkwardly in one’s chair is none of those. However, its awkwardness makes it one of the potentially more memorable points of the Seder. Tradition creates its own meaning.

We could ask the same thing of our "Bread of Poverty" statement. How can one hold up an Ashkenazic perforated cracker and claim that "this is the bread" our ancient Israelite forebears ate? It's like if we were to hold up a bottle of Coca Cola, and said, "This is what our ancestors drank..." This kind of matzah surely does not resemble in the slightest the unleavened bread of the ancient world. But again, the point is not to attempt to accurately recreate the historical reality. Rather, it's to imaginatively create a story which impacts our conscious reality.

Not accurately but imaginatively. Not recreate but create. Not history but story. Not objective reality but conscious reality. And I'll add: Not memory but sacred memory. Sacred memory includes 1) the collective memory of the people, wherein kernels of historical memory are fashioned into sacred stories that are passed on and shaped throughout time, and 2) the memories we produce with our own families. The specific set of traditions we experience year after year - the songs, the foods, the mishegoss, the dynamics among various family members, the quirky traditions which our family has and which over time become inexplicably beloved - that is what makes our memories of the Seder sacred.

הָא לַחְמָא עַנְיָא דִּי אֲכָלוּ אַבְהָתָנָא בְּאַרְעָא דְמִצְרָיִם

כָּל דִּכְפִין יֵיתֵי וְיֵיכוֹל

כָּל דִּצְרִיךְ יֵיתֵי וְיִפְסַח

הָשַׁתָּא הָכָא, לְשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה בְּאַרְעָא דְיִשְׂרָאֵל

הָשַׁתָּא עַבְדֵּי, לְשָׁנָה הַבָּאָה בְּנֵי חוֹרִין

This is the bread of poverty that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.

Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat.

Whoever is in need, let him come and partake in Passover.

This year [we are] here; next year in the land of Israel.

This year [we are] slaves; next year, free people.

What matzah are we talking about here?

When the Torah refers to matzah, it's talking about what the Israelites ate while leaving Egypt, when they didn't have time to wait around for the dough to rise, etc. But if that were the matzah under discussion, not only should the text have said that it's the bread we ate "while leaving Egypt" rather than "in the land of Egypt," but it would rightly be called the "bread of freedom" rather than the "bread of poverty."

This matzah we hold up represents something the Torah doesn't actually speak about, an unleavened bread eaten while enslaved, hence "the bread of poverty" eaten "in the land of Egypt." Why does the Haggadah refer to matzah that's different from the one everyone knows about in the Exodus story? And why suppose that our ancestors even ate matzah at all during slavery?

Ancient Egypt was famous for its fermented grain technology, perfecting the use of sourdough starter (se'or in Hebrew) and eventually isolating yeast cultures. It was an important craft and trade. There were royal bread makers. The type of bread you ate went along with your status. Leavened breads made with fine flour were a high society item, and they were used in ritual offerings to the gods.

Although the Torah likewise calls for solet (fine flour) in the mincha sacrifice, it prohibits using chametz (leaven) in sacrifices. According to Jacob Milgrom (Anchor Yale Bible, Leviticus Vol I, pp. 188-9), the reason for this prohibition is that chametz was considered a symbol of "corruption." But perhaps that stems in part from a perception about Egyptian practices being corrupt, and leaven being symbolic of Egypt. And of course the Torah also prohibits the consumption of leaven during Passover. Not only that, but it warns against seeing or finding leavening agents in our homes, lest we be "cut off" from the people. Perhaps these laws are less a reflection of the "leaving Egypt" aspect of matzah, explicit in the Torah, and have more to do with the implicit "Egyptian society" associations of chametz.

The Torah's stringency about leaven may be saying that it's simply not fitting to celebrate our liberation from Egypt while at the same time partaking of the quintessential Egyptian product. Perhaps it would be something like eating bratwurst and sauerkraut, or other iconic German foods, during a time specifically set aside to commemorate the liberation from Auschwitz - an act of dis-identifying with the Jewish people. In the same way, eating leaven on Passover might have been viewed as "cutting oneself off" from the people.

But it also explains why matzah here is called the "bread of poverty," not the "bread of freedom." This particular bread is symbolic of the underclass of Egypt - the poor and enslaved. I say "symbolic," as opposed to asserting that the Egyptian underclass only ate unleavened bread. Surely they ate chametz, simply by allowing their dough to stand for 18 minutes, and they used se'or/sourdough starter, as evidenced by the Torah telling the Israelites to remove the se'or from their homes. But matzah is physically "lowly" bread, "impoverished" in both form and taste, and hence symbolic of the slave class.

It's a beautiful transformation then that this bread ended up, by way of the exodus, representing freedom. It is freedom not only in the sense of being eaten "on the way out" of Egypt, but freedom also by not being chametz and thereby constituting a rejection of that which symbolizes Egyptian society, a civilization we recall for its systematic enslavement and brutality.

Isn't it incongruous to say "next year in the land of Israel"?

One might in fact argue that, living as we do with full access to a sovereign Jewish state after 2000 years, that it's not only incongruous, negating historical reality, but a show of extraordinary ingratitude to say the statement, "Now we are here; next year in the land of Israel."

But of course such an interpretation ignores the preceding statement, "Now we are slaves; next year, free people." Meaning, both statements are in the frame of make-believe, imagining ourselves to be slaves in Egypt. It's like the statement said later in the Haggadah: "If the Holy One, blessed be He, had not taken our ancestors out of Egypt, then we, our children and our children's children would have remained enslaved to Pharaoh in Egypt." Would we really? 3,300 years later, people around the world would be on Facebook, planning manned voyages to Mars, and watching the Kardashians, and meanwhile in Egypt there would still be a Pharaoh with us as his slaves? Obviously not. It's a statement of severity that's intended to set the mood, to put the image in our minds of our families, our children, being slaves.

The point of the Passover Seder, and recounting the narrative of the exodus from Egypt, is not to achieve maximal historical veracity and authenticity, but to ritually recall our national story, the way we choose to remember it, and that refers both to "what" we say and "how" we say it.

Think about the last of the four questions: "On all nights we eat sitting upright or reclining, and on this night we all recline."

Here's a place where we truly feel the gap in history. Unless we're talking TV dinners on the sofa, very few people eat reclining. If anything, eating while lying down reminds us of being infirmed, sickly. We’re so used to eating upright that it seems strange and even awkward to try to eat while reclining. Even the pillow we add to our chairs doesn't necessarily make it more comfortable or "luxurious." And to sit in a chair and lean to the left out into the air, when drinking the four cups and eating matzah, is truly bizarre. The "authentic" thing to do would be to lie down on one’s side and eat. The conceptually "meaningful" thing to do would be to eat in the most comfortable, luxurious way possible, which ironically for most people would mean sitting upright in a chair. Leaning awkwardly in one’s chair is none of those. However, its awkwardness makes it one of the potentially more memorable points of the Seder. Tradition creates its own meaning.

We could ask the same thing of our "Bread of Poverty" statement. How can one hold up an Ashkenazic perforated cracker and claim that "this is the bread" our ancient Israelite forebears ate? It's like if we were to hold up a bottle of Coca Cola, and said, "This is what our ancestors drank..." This kind of matzah surely does not resemble in the slightest the unleavened bread of the ancient world. But again, the point is not to attempt to accurately recreate the historical reality. Rather, it's to imaginatively create a story which impacts our conscious reality.

Not accurately but imaginatively. Not recreate but create. Not history but story. Not objective reality but conscious reality. And I'll add: Not memory but sacred memory. Sacred memory includes 1) the collective memory of the people, wherein kernels of historical memory are fashioned into sacred stories that are passed on and shaped throughout time, and 2) the memories we produce with our own families. The specific set of traditions we experience year after year - the songs, the foods, the mishegoss, the dynamics among various family members, the quirky traditions which our family has and which over time become inexplicably beloved - that is what makes our memories of the Seder sacred.

Comments

Post a Comment

Not sure how to leave a comment? By "Comment as", either choose your Google ID, OR select "Name/URL". Type your name and leave URL blank (if you don't have a web address). Then hit "Publish", type in the letters/number shown, and again "Publish". I don't mind anonymous comments, but please use a pseudonym.